The other day I was lucky enough to be able to attend the 223rd American Astronomical Society meeting in Washington, D.C . I say lucky because a) I’m a nerd and b) this conference normally costs approximately $600 to attend if you’re not a member of the AAS, but I fortunately got in for free, thanks to my dad. It’s also physically impossible to actually get to – when I say it was held in Washington, D.C., I really mean National Harbor, Maryland, aka the metro-less, bizarre, Stanley-Kubrick-esque hotel that holds several thousand people and only one observable coffee shop. No one would ever go there unless forced, and they’d still have to have a car with GPS.

Anyways, right: SPACE. There’s a whole lot of it and a whole lot of research going on about the nature of gravity, pulsars, quasars, dark matter, dark energy, luminosity polarimetry, and everything else that’s fascinating and confusing. Astronomers are finding extra-solar planets like it’s their job (oh wait…) and giving them names like Kepler 406 and GJ1214b and KOI-314c. The discover of that latter planet, about 200 light-years away from us, is actually really exciting because it has the same mass as Earth – a rare find, despite the plethora of planets that have been discovered outside our solar system. For whatever reason, Earth seems to be a rarity in its dimensions; most other planets that we’re finding (I’m saying we as if I’m helping… brilliant astronomers, I should say) fall somewhere between Earth and Neptune’s size, Neptune being about four times the size of Earth.

The astronomers I met are absolutely certain that we could find life on other planets in the next couple decades – if NASA and other agencies receive proper the funding to develop technologies. And that’s a big “if.” The telescopes they’re talking about building would cost around $6 billion. There would have to be an enormous push from the public to get that kind of funding.

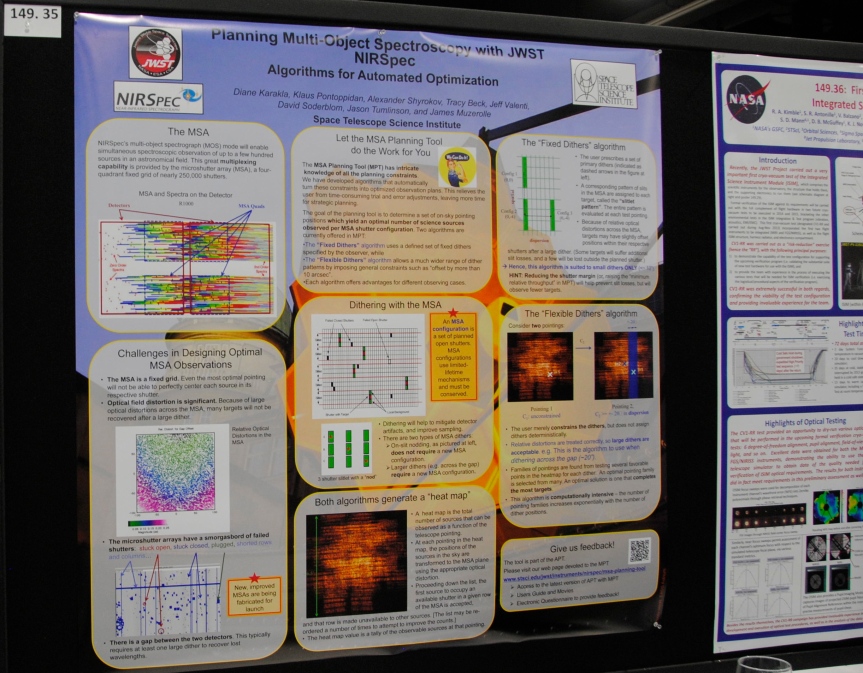

But the astronomers are optimistic, and the conference had a tangible excitement in the air, a real community buzz – you could tell that everyone there was either friends or going to be friends by bonding over their obsession with space. As I walked through the field of posters on the lower level – there must have been about 500 posters in there – I felt like a total oddball, like I was orbiting the outskirts of something really important and yet completely inaccessible and incomprehensible to me. What are these mysterious words printed on the boards – surely not English? What was I doing here, again? Why did I feel like the only non-astronomer out of thousands of people, anyway?

I left feeling both excited by the prospect of future space exploration, and discouraged by how little I understood about this realm of science. There is so much about the universe that I don’t understand, not even remotely. And most of all, I felt stupidly lucky to have had the opportunity to meet Geoff Marcy and other scientists who have the talented knack for getting others jazzed about the potential for finding aliens and exploring our galaxy (as well as others) in the future. There are some really smart, engaging, passionate scientists out there who are powerful communicators, when seen in person; but had I not been with my dad, there was no way I would’ve known about them, nonetheless met them.

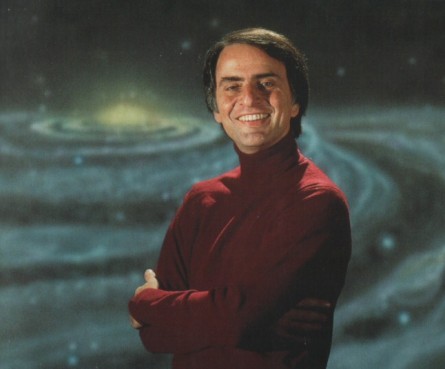

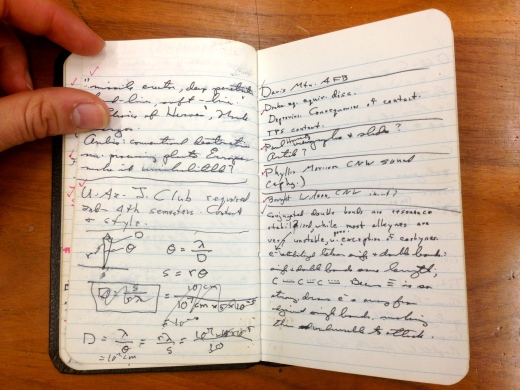

For the past several months, I’ve been exploring the Carl Sagan collection in the Library of Congress, which contains every letter, essay, photo and piece of fan mail from this famous astronomer’s life. More than anything, the archive has shown me just how much of an impact Sagan had on the public. He was a true figurehead in the Space Age (an age that is very much in the past, unfortunately); he was so famous that he’d receive hundreds of letters a day, from anyone ranging from Jimmy Carter to the crazies. Sagan was able to inspire every kind of person, from scientist to artist, philosopher to poet, to think about their place in the universe.

Sagan passed away in 1996, and the past 18 years have been all but silent of a public figurehead explaining complex astronomy concepts (with the possible exception of Neil deGrasse Tyson). I don’t blame the astronomical community for this – in fact I think there are real figureheads that have similar talents and passions to Sagan. Rather, I blame the way media is structured now, as opposed to 20 or 30 years ago.

Think about it: Sagan became famous with his TV series, Cosmos. He could engage every American at the same time on the same day with his talented conviction about scientific concepts. These people could then go and talk about the fascinating ideas the next day with their friends or co-workers. This is a conversational-driven system of sharing knowledge, where information is passed through passionate speech.

Look at our world now. We live in a world saturated in online articles, YouTube videos, blog posts and tweets. We are constantly bombarded by information, including scientific information. But I would argue that these only pull in people who are already science nerds and avid followers of science news. A clever twitter feed about biology will never, ever inspire the average citizen to suddenly pick up Stephen Jay Gould’s Wonderful Life, nor will a Facebook post about a new galaxy cluster prompt a Facebook user to watch the television show called… oh wait, there aren’t any well-known TV programs devoted to astronomy (at least, not to my knowledge).

I think it’s easy to think that the Internet solves many problems relating to communicating science, but I’ve found in my own life – and I’m pretty sure I’m not unique in this – that the information on the Internet is a poor substitution for information from a person-to-person conversation, or even a well-written book. The Internet will never replace a voice like Sagan’s, one that you can hear and see and connect with on an emotional level. (I realize I say this as I passionately type away for my blog which has very few followers… but I’m not pretending like life isn’t ironic). People don’t use the Internet to gravitate towards unknown subjects. They use to find things that they’re already interested in.

So it occurs to me that a convention like the one I attended – which is chock-full of brilliant and engaging astronomers – are exactly what astronomers are looking for as they want to gain public support for space missions and telescope development etc. In other words, these mass gatherings, if open to the public, could be a way for people to become excited about discovering the cosmos, and re-launch the Space Age. My generation doesn’t have a Carl Sagan. We didn’t witness the first man on the moon. We need a different way of connecting with science now.

If the AAS just made one of their four days free and open to the public (and held the meeting in a location that was actually accessible!), they could potentially drive a lot of public interest in astronomy development. I really do believe that astronomers could find extra-terrestrial life in my generation, if they were given enough funding to develop and implement the powerful technology that it requires. But without obvious support from the public, it strikes me as unlikely that these scientists will get a grant for six billion dollars, at least not anytime soon.